The UIAA’s Summit Series explores a number of the world’s most iconic and challenging mountains and mountain ranges. Produced by the UIAA Medical Commission, they offer information on numerous areas including ascent profiles, acclimatization and preparation. The papers also offer links to live information and introduces other useful areas of UIAA expertise.

About Denali

Alaska’s Denali (6,194 m) has a set of unique characteristics that are known far and wide across the mountaineering world. The low altitude (~700 m) from which it rises, just 3° south of the 66°6’N latitude Arctic Circle, gives it a singular distinction amongst the world’s mountains. Denali’s closest 6,000 m rival in terms of latitude is in central Asia, at just 39°N. This ensures that Denali is not only the coldest of the 6,000 m mountains, but is vulnerable to the violent storms that head south from the Arctic and gather in the nearby Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea.

Denali is the highest peak on the North American continent and as such is a highly desired objective for more than a thousand aspirants each year. Even in the face of relatively large numbers, mainly on the West Buttress route, the United States National Park Service (NPS) has tried to encourage a philosophy of self-sufficiency amongst mountaineers whenever possible. In this article we’ll discuss a logical and tried approach to an ascent of the West Buttress route and identify many of the problems you’re likely to encounter along the way.

The US NPS has provided a comprehensive website devoted to climbing in Denali National Park, focusing on Denali (the mountain) itself. But it also covers many other aspects of climbing and backcountry travel throughout different areas of the Alaska Range.

Ascent of the West Buttress Route

Access

The vast majority of climbers access Denali via single-engine aircraft fitted with skis from the Alaskan town of Talkeetna – a 40-minute flight away. Alternatively, it is possible to walk directly to the mountain. However, expect to spend at 5-7 days walking with huge loads across mosquito-infested tundra and large glacial river crossings before you reach the mountain. The Alaskan adage of “fly an hour or walk a week” certainly applies here. Talkeetna is a 2.5-hour drive north of Anchorage. Please refer to:

- NPS website for available aviation and support services https://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/support-services.htm

- Anchorage to Talkeetna shuttles: https://denalioverland.com/

- Those who prefer train travel may also ride a bus or the Alaska Railroad from Anchorage to Talkeetna. However, train times are not always convenient and it can cost considerably more than a shuttle.

https://www.alaskatravel.com/transportation/anchorage-talkeetna/

Route Description

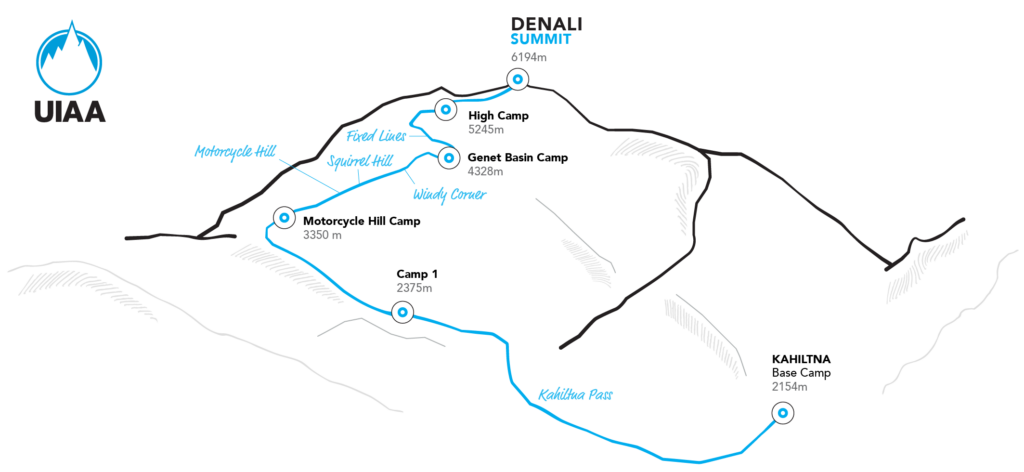

Since most international flights arrive late at night in Alaska, most expeditions spend at least one night in Anchorage. Once in Talkeetna, you’ll need to repack and load your equipment onto the ski plane. Most air taxi operators will allow 50 – 60 kg of gear per person. The plane will drop you at 2,200 m, so wear clothing suitable for glacial travel (including boots). If your flight reservation and appropriate weather window coincide, you’ll soon be on your way. However, climbers may need to wait several days if the weather does not cooperate. But eventually you’ll be airborne, enjoying the beautiful views over the Kahiltna Glacier, before landing in Base Camp (2,200m)

On Denali, as well as many other Alaskan mountains, sledges are the only effective way to reduce the weight of your pack and ease the huge burden of moving your expedition supplies across the glacier. Some climbers utilize expensive, specially made metal sledges, but plastic “kiddie” sleds available from your air taxi operator will work fine, provided one remembers some basic points about their use:

1) Pack heavy items on the bottom, lighter items on top. Use one or more duffel bags that are securely attached to the sled with accessory cord.

2) Do not put all food, fuel, tents or other group gear in one sled – divide such items among the group. If a sledge is lost down a crevasse, your expedition will come to a very premature end if you haven’t divided up your gear.

3) It is recommended that a least the lead person on a rope team hitches their sled to the climbing rope behind them – this may prevent the sledge from dropping on top of you in the event of a crevasse fall.

Managing both a sledge and backpack, whilst wearing skis or snowshoes and being roped together, takes a bit of getting used to. However, you will get plenty of practice since it’s best to travel in roped, glacier-travel mode as far as Basin Camp at 4,300m. At this point the sledges can be cached until your descent. Whilst the crevasse danger lessens above this point, most parties elect to stay roped together for the duration of the climb.

Camp 1 is established at 2,375 m at the confluence of the main Kahiltna Glacier and the heavily crevassed Northeast Fork (3-6 hours from the Kahiltna Glacier airstrip). Many climbers start to “ferry” loads between camps at this point so as to reduce the weight they are moving at one go. Importantly, this process also slows down the rate of ascent and allows for a more gradual acclimatization to the altitude. In addition, the repeated load carries are especially enjoyable for those wearing skis. The downhill skiing is especially good between Camp 1, the Camp at Kahiltna Pass (2,950 m) (climb from Camp 1 to Kahiltna Pass is 2-5 hours) and Motorcycle Hill Camp (3,350 m) (climb from Kahiltna Pass to Motorcycle Hill Camp is 2-4 hours). Downhill skiing while roped up is difficult but is highly recommended in heavily crevassed areas.

Above Motorcycle Hill Camp at 3,350 m, the climbing steepens as the route takes you past the terminal walls of the West Buttress. Many will opt to cache skis or snowshoes at 3,350 m and continue the climb with crampons and a single ice axe (with perhaps a ski pole in the other hand for additional support) since the route steepens here and the snowpack hardens. You’ll then have to climb steeply out of a basin in order to reach Windy Corner at 4,115m, and then make an ascending traverse through seracs and heavily crevassed terrain to approach the head of the Kahiltna Glacier and Basin Camp at ~4,300 m (climb from Motorcycle Hill Camp to Basin Camp is 4-8 hours) . As you look down to the lower Kahiltna Glacier and out to 5,300 m Mt. Foraker the views are spectacular. In the opposite direction the impressive summit bulk of Denali rises above you, and the details of the upper West Rib and Messner Couloir are clear, as is the steep headwall of the West Buttress that you’ll soon be climbing. At Basin Camp (4,300 m), most groups take a rest day, since time is needed to make final preparations for your summit bid and the load carrying that you’ll need to do in order to be ready for high camp and beyond.

At this point you’re about to embark upon the most demanding part of the climb – with higher, colder territory combined with steeper and more exposed ground providing a fierce test of skills and stamina. From Basin Camp, you ascend approximately 300 m up a gentle snow slope to the bergschrund at the base of the West Buttress. The bergschrund is at times quite steep but it is short and, with steps established in the ice, not difficult to surmount. The ascent of the West Buttress now begins via the 300m headwall that lies in front of you. The angle of this slope is 45 to 50 degrees and care needs to be taken. Typically, the pitches are hard ice with some overlying snow. It is possible to protect this section with jumars since a fixed rope is placed every season with the assistance of the NPS and local guides. Because of the steepness of the route and the amount of altitude gained, most parties make a double carry to establish Ridge Camp at just over 5,000 m (climb from Basin Camp to Ridge Camp is 2-3 hrs).

Emerging from the headwall onto the top of the Buttress, the atmosphere of the climb changes dramatically. The exposure is considerable. As you begin to move along the crest of the Buttress, views spread north across the Peters Glacier to the Alaskan tundra and south to the scores of other peaks in the Alaska Range. These vistas are spectacular in clear weather. Initially the ridge is fairly broad, but gradually it narrows, with steep drop-offs to both sides.

The traverse to High Camp (at 5,245 m) follows a steadily narrowing crest and at times moves between and around a series of magnificent, pointed granite gendarmes up to 20 m high. The climbing is never steeper than 35 degrees, but the exposure is significant and requires caution, especially in high winds, as you move up a route that in some sections is reduced to ledges just one or two metres wide. Close to High Camp the ridge finally begins to merge with the main part of the Denali massif, and soon you’ll establish camp in a basin just below Denali Pass, the low point between Denali’s higher south summit and the slightly lower north peak (climb from Ridge Camp to High Camp is 2-5 hours). From here you will climb to the summit in a single day.

On summit day you’ll make an ascending traverse to Denali Pass, and en route overcome a fairly steep section between 5,360 and 5,490 m. From there you’ll climb gentle slopes to a plateau at 5,910 m, from which you get impressive views down onto the Harper and Muldrow Glaciers and across to Denali’s North Peak. The final approach to the summit climbs moderately steep slopes to the crest of the ridge between Kahiltna Horn (6,130 m) and the main summit. At the crest you can peer down the 2,400 m drop of the precipitous South Face, looking between the Cassin Ridge to your right and the South Buttress to your left. From here you’ll ascend the summit ridge on its exposed south side, before switching to north side for approximately 200 mostly horizontal meters to the clearly defined 6,194 m summit of the highest mountain in North America. Plan on 8-12 hours from High Camp to the summit. Keep an eye on the weather and abort the climb if bad weather is approaching. You do not want the highlight of your climb to be getting caught in a storm near the top of Denali – it has on many occasions been a deadly experience for those who ignore changing weather high on this peak. Bad weather above 5,000 m on this mountain is a serious proposition. Whiteouts are common and wind chill factors can often be extreme.

See an essay titled “Thoughts from a Retired Mountaineering Ranger” that drives home this point

https://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/survival.htm

Duration

The time from Kahiltna base to the summit and return is usually accomplished in 14-21 days. The decision when and where to make double carries between camps and take rest days for acclimatisation are up to you. However, “storm days”, when you are confined to your tent, are beyond your control. Ensure that you have incorporated some extra days into your schedule to allow enough time to sit out a multiple-day storm (or two).

Essentials

Language

English

Local Currency

US Dollar

Visa Requirements

For visa requirements please refer to your country’s US embassy.

Nearest Hospital

Providence Alaska Medical Center and Alaska Regional Hospital in Anchorage both offer full-service, comprehensive care.

Evacuation

Basin Camp at 4,330 m is the site of a NPS climbing ranger encampment and is occupied from late April to early July. In addition, there is normally a medically-trained individual working on the rotating ranger patrols that crisscross the mountain throughout the season. This is an emergency “facility” – do not rely on the NPS for first aid supplies and other things which should be a normal part of your expeditionary kit. The NPS Search and Rescue Policy states that rescue operations are conducted on a discretionary basis. There is an expectation that Park users will demonstrate a degree of self reliance and responsibility for their own safety as regards extracting themselves from problems. Helicopters configured for high altitude rescue are used for urgent evacuations, but the nature of the weather, distances involved, and availability of rescue personnel on Denali makes this a different situation than, for instance, rescue in the European Alps. Parties are better off performing self-rescue if at all possible – one is better off realizing straightaway that Denali is not a place to expect the sort of “rapid response” rescue service routinely seen in Zermatt or Chamonix!

Climbing Seasons

The standard climbing season is late April through early July. However even in late April it can still be very cold – normal night time temperatures at 4330 m in April are minus 30 or 40°C. Those who climb prior to early May should be prepared for winter-like temperatures and minus 50°C (or less) on the upper mountain. As a general rule, the springtime is typically clear and cold – but windy – with Arctic air masses predominating, and as summer approaches a moist southerly air flow from the Gulf of Alaska takes over. The majority of climbers elect to come to Denali at the time of the seasonal shift (late May to early June) where hopefully they’ll get both clear weather and mild temperatures. It is certainly possible to climb after early July, but the aviation companies usually begin to limit flights to the Kahiltna Glacier at that time since open crevasses start to appear on the runway. If you think you might enjoy walking a week or more in to the climb or out to civilization through mosquito infested tundra and across big glacial rivers – not to mention dodging Grizzly bears – climbing in the latter part of the season has its advantages. The temperatures are often warmer and you’ll benefit from the 20+ hours of sub-arctic summer daylight.

Communication

CB radios are widely used on Denali, and both the NPS and the Base Camp Manager on the Kahiltna Glacier monitor channel 19. These radios normally rely on line-of-sight, however. Mobile phones often work well at Basin Camp and above, provided your phone service provider has a roaming agreement with an Alaskan telecom company. Satellite phones are another option, but only Iridium has reception – Thuraya does not work on Denali.

Conditions

As already suggested, Denali can be a very cold place. However, below approximately 3000 m on the mountain later in the season, it can get very warm. At midday it can feel like you’re trapped in a solar oven. As summer nears, parties below 3000 m often choose to travel at night. Although it is much cooler, it is rarely too cold and there is often sufficient light by which to travel. Because of factors such as the tremendous vertical relief of Denali, high latitude, and closeness of the ocean, mountain storms here are legendary. Be prepared to be hit by a couple of storms during the course of the climb. If you are lucky, they may be mild and last only 24 hours or so. However a severe 5-7 day pounding from a single storm system is not unheard of by any means. Be prepared.

Technical Difficulty

The West Buttress is technically straightforward. Nevertheless, you’ll need to be familiar with roped glacial travel, exposed ridge walking and climbing short, steep sections of 40-50 degree snow and ice. The steepest sections of the route, between Basin Camp and Ridge Camp, are protected by fixed ropes. The use of a jumar or other type of ascender is recommended. At times you’ll feel that the real difficulty of the route is to be found in shifting your kit up and down the mountain. Unfortunately, heavy packs and sledges are the order of the day.

Environmental Considerations

and Mountain Protection

The UIAA is committed to the protection of the mountain environment and has been since its founding in 1932. The UIAA Mountain Protection Commission was formed in 1969. Today the UIAA spearheads a number of projects related to sustainability in mountain regions including its annual Mountain Protection Award, through the work of its Climate Change Taskforce and its many international partnerships. For further details please visit: https://theuiaa.org/mountain-protection/

The UIAA encourages all climbers and mountaineers to consider their carbon footprint and adhere to local regulations and customs once on the ground.

Specific environmental considerations for Denali can be found here: https://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/cleanclimb.htm

Dangers

The majority of the danger on Denali stems from the high altitude and sub-arctic environment. The incidence of high-altitude illness on the mountain is exacerbated by the physiological stress of the hard work needed to haul heavy loads in a very cold environment. Allow sufficient time for acclimatization and enough storm days so that you don’t have to rush your ascent.

See this article for guidance on a suitable ascent profile. The cold, especially early in the season, can be so intense that frostbite is an ever-present danger. Other routine mountain-related hazards such as falls and avalanches must also be considered, but altitude illness and frostbite are by far the most commonly encountered problems for climbers.

Using Safe Climbing Equipment

A demanding climb like Denali requires significant preparation, training and planning. It also requires having the right equipment. The UIAA encourages all climbers to purchase certified equipment. The UIAA Safety Label is the only global certification for climbing equipment.

The UIAA Safety Label on a piece of climbing equipment means that samples of the equipment have been tested by an accredited, independent third party and shown to satisfy the requirements set forth in the UIAA standard. UIAA standards exist for over 25 times of climbing gear including ice axes, ropes and crampons.

Climbers can search for certified equipment through the UIAA’s dedicated database. Furthermore, the UIAA offers information on how best to purchase climbing equipment.

UIAA Skills Guide

The UIAA is committed to providing climbers and mountaineers with information to develop their skills, whether reinforcing lessons learned and not yet fully assimilated or to increase their technical knowledge and reduce the risks inherent to our sport. The UIAA Alpine Skills Summer guide was first published in 2015. Produced in collaboration with the Petzl Foundation, the guide and has been well received worldwide and is currently available in over ten languages. It covers a host of topics from route planning to frostbite, to reading the weather and climbing in a group. A winter version of the guide will be released shortly. The English language version can be purchased as a digital download here. Foreign language versions are available through UIAA member associations.

Additional UIAA

Medical Resources

MEDICAL ADVICE

Further Reading

Lead Author – George Rodway

Images – courtesy of George Rodway and Stock Library

All text and content is reviewed by a dedicated working group within UIAA Medical Commission. Discover more here.

For additional advice on high altitude illness, please refer to:

https://www.wms.org/magazine/1252/2019altitude-cpg/default.aspx?WebsiteKey=02116d8c-0957-4e16-b702-f027569c7211

For advice on frostbite, please refer to:

https://www.wms.org/magazine/1250/frostbite-cgp/default.aspx?WebsiteKey=02116d8c-0957-4e16-b702-f027569c7211

There has also been a considerable amount of literature published on climbing (and surviving) Denali see:

https://www.nps.gov/dena/planyourvisit/books.htm

Going to this mountain well-informed and prepared for whatever the high, sub-arctic environment might throw at you is most certainly worth the investment of your time and effort.

For those interested in recent analyses and discussion about Denali appearing in peer-reviewed medical journals, see:

McIntosh SE, Campbell A, Weber D, Dow J, Joy E, Grissom CK. Mountaineering medical events and trauma on Denali, 1992-2011. High Alt Med Biol. 2012; 13(4):275-80.

Rodway GW, McIntosh SE, Dow J. Mountain research and rescue on Denali: a short history from the 1980s to the present. High Alt Med Biol. 2011;12(3):277-83.